June feels like it flew by, and apart from celebrating our ‘Daneaversary’ (two years in Denmark) with some friends, there’s not a lot to report on. Therefore, I wanted to share a story with you of a field trip in Australia (2021) that I had the pleasure of joining in on. Enjoy! But first

Summer in Copenhagen

Early June gave us our first warm summer’s day – a sunny, pleasant, 25-degree day where we made sure to get out and about for a bike ride on the local island of Amager. Construction continues in Carlsberg – though there are definitely fewer cranes around than when we arrived.

© 2024. This work is openly licensed via CC BY-NC 4.0

© 2024. This work is openly licensed via CC BY-NC 4.0

© 2024. This work is openly licensed via CC BY-NC 4.0

© 2024. This work is openly licensed via CC BY-NC 4.0

A hop, skip, and a bounce (retrospective)

Ask someone living across the world what they think of when they hear ‘Australia’, and chances are they’ll say ‘kangaroo’. Australia is indeed home to an amazing biodiversity, with many animals found nowhere else on the planet. It’s no surprise then that Australia is known for its rich and ‘exotic’ animal life. Have you heard of a wallaby? If the answer is ‘yes’, you’d likely think that they are a small type of kangaroo – and you’d be right! The term ‘wallaby’ is an informal one used to refer to small or medium-sized members of the ‘Macropodidae’ – a family of Australian mammal that contains ‘Skippys’ of all sizes. From the strapping red kangaroo, clocking in at up to 85 kg (!), to the tiny mala (rufous hare-wallaby), weighing in at around 1 kg. Lesser known is the yellow-footed rock wallaby, the focus of this story.

Into the outback

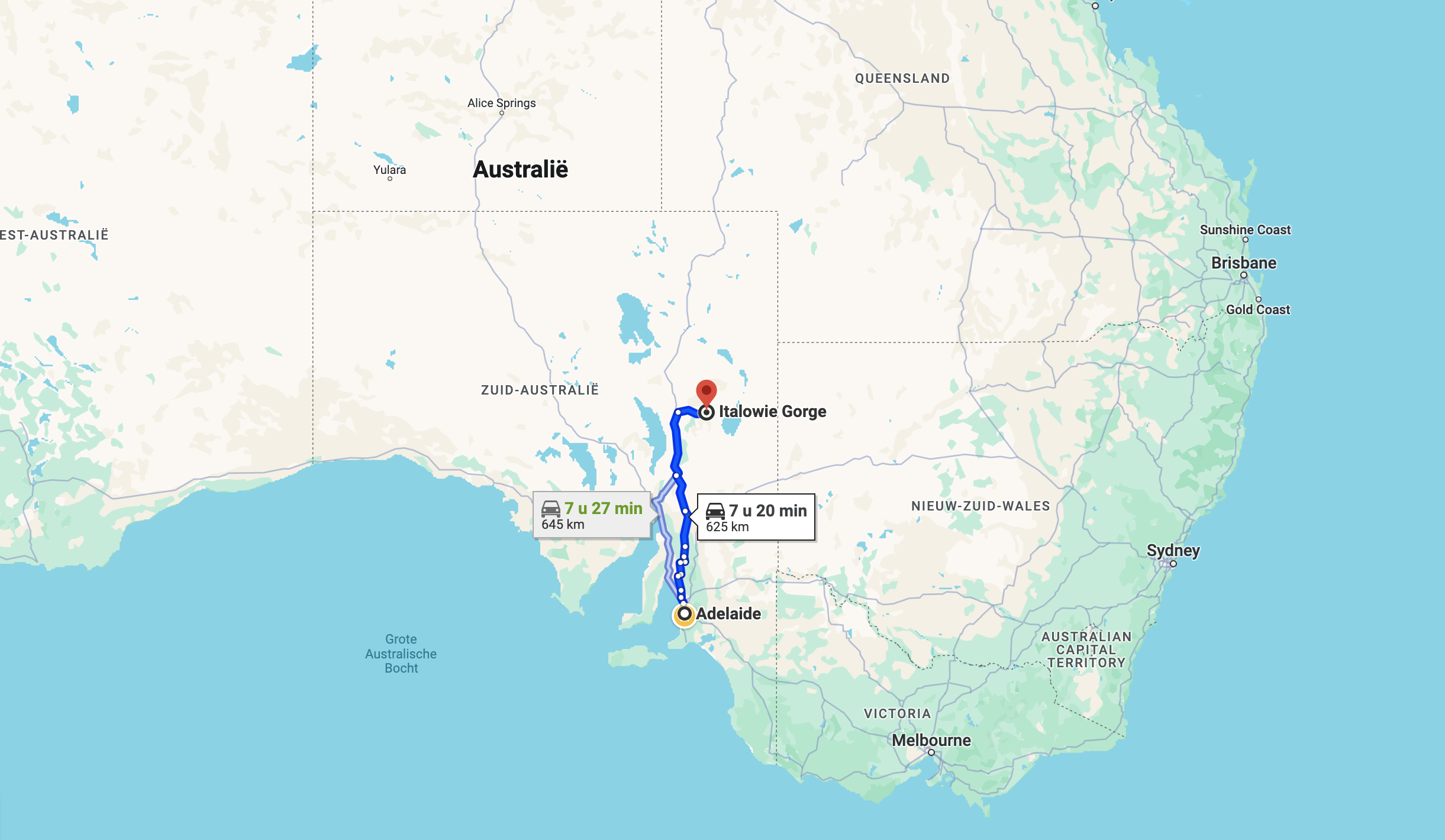

It starts with an early morning; the sky is clear, and the day promises temperatures of low 20s – perfect for a long drive into the outback. A white 4WD ute (pickup truck) – with large trailer in tow – rolls down the driveway. The crew is here to pick me up: Chloe, Shannon, Lauren and Tags. ‘G’days’ are exchanged, my gear is loaded, and we’re on the road north. Our target: the spectacular Vulkathunha-Gammon Ranges National Park ~600 km north of Adelaide, home to the elusive and vulnerable yellow-footed rock wallaby (YFRW). Our mission: to check in on the local YFRW population, a part of Lauren’s PhD project.

As with many of Australia’s native mammals, the YFRW is listed as vulnerable. The YFRW was considered a common feature of the arid landscape a century ago. However, a mixture of historical hunting for its beautiful fur, overgrazing of its habitat by feral introduced herbivores (e.g. goats), pressure from invasive predators (foxes), and human land use change have seen the YFRW’s population drop. Thankfully, the Bounceback program led by the National Parks and Wildlife Service SA and other partners has seen a steady recovery of the YFRW and its habitat. Established in 1992, this program has seen a 10-fold increase in the numbers (~2,000) and areas occupied by YFRWs in South Australia.

© 2024. This work is openly licensed via CC BY-NC 4.0

Our drive sees us passing urban/suburban Adelaide, vast agricultural fields, and takes us past Goyder’s line, north of which annual rainfall doesn’t support cropping. From here onwards, we’re met with stunning, rugged landscapes, and see some of the local wildlife that make a living up here.

© 2024. This work is openly licensed via CC BY-NC 4.0

© 2024. This work is openly licensed via CC BY-NC 4.0

© 2024. This work is openly licensed via CC BY-NC 4.0

© 2024. This work is openly licensed via CC BY-NC 4.0

After a long drive – the last hour and a half down rough gravel trails – we arrive at our accommodation for the week: a humble, thick-walled cottage, which I presume was built as a homestead for workers in the wool industry (yes, people farmed merino wool this far north!). It’s late afternoon: we’ve still got a few hours of daylight left, but it’s not time to relax just yet.

The traps are set

As their name suggest, rock wallabies live in rocky areas that afford them a degree of safety from predators. Looking around, I’m amazed at the habitat that they call home – rugged rocky outcrops and vertigo-inducing cliff faces.

© 2024. This work is openly licensed via CC BY-NC 4.0

© 2024. This work is openly licensed via CC BY-NC 4.0

© 2024. This work is openly licensed via CC BY-NC 4.0

© 2024. This work is openly licensed via CC BY-NC 4.0

How does one catch a YFRW in this environment? Traps. The only problem: we need to lug them up to where they live. While we get to work, I get the feeling that we’re being watched. While hoisting the traps up these cliffs, we occasionally hear a few rocks tumbling in the distance – likely signs of the local YFRWs hopping about.

© 2024. This work is openly licensed via CC BY-NC 4.0

After a couple of hours of grunting and sweating, the traps are set, and we bait them with a mixture of apples and peanut butter oat balls (a trusty recipe). Sniffing, I get a strong whiff of anise. Shannon sprays some rocks around the traps with a scent that supposedly piques the YFRWs’ natural curiosity.

© 2024. This work is openly licensed via CC BY-NC 4.0

© 2024. This work is openly licensed via CC BY-NC 4.0

Back at camp, knackered after a long day’s drive and trap setting, we head to bed.

Up close and personal

We’re up before dawn, as we need to release the YFRWs from their traps before it gets too hot. The morning is fresh, but there’s a promise of heat as the sun rises. After a quick brekky and tea, we’re back on the road towards the trapping site. While we climb to check in on the traps, we see the beautiful landscape brighten as the sun rises and hear the birds make their morning calls.

© 2024. This work is openly licensed via CC BY-NC 4.0

© 2024. This work is openly licensed via CC BY-NC 4.0

© 2024. This work is openly licensed via CC BY-NC 4.0

Caught wallabies are transferred to a thick cloth sack, and thrown over shoulders (they weigh ~6-12 kg) as we take them to our makeshift processing site – a foldout plastic table surrounded by some ancient fallen logs. Measurements are taken: weights, the lengths of body parts, and genetic and microbial samples (faeces and pouch swab)

© 2024. This work is openly licensed via CC BY-NC 4.0

© 2024. This work is openly licensed via CC BY-NC 4.0

© 2024. This work is openly licensed via CC BY-NC 4.0

Occasionally, we’d come across an amazing sight – pouch young (joeys) developing in their mothers’ pouches. Wallabies, like most native Australian mammals, are marsupials (from Latin/Greek marsupium, meaning pouch). The pouch is a key defining trait for marsupials, which are typically born very young (after only a few weeks), and start life with an epic journey from the birth canal to the safety of the mothers pouch see video. Marsupials are our distant relatives, with estimates that we shared a common ancestor ~160 million years ago (when dinosaurs ruled the planet)

© 2024. This work is openly licensed via CC BY-NC 4.0

Measurements made and samples taken, the wallabies are brought back to where they were caught and released – putting myself in their (big) shoes, I can only imagine it being similar to abduction by aliens!

The other locals

With a hard day’s work done, we went to check in on the other locals – this time, in a more familiar (and less vertically demanding) urban habitat. Arkaroola, a short 700 km north of Adelaide, is a wildlife sanctuary and cozy township. Established in 1968 by geologist Reg Sprigg, Arkaroola has become a base for intrepid travellers wishing to get a taste of the South Australian outback. This tiny town hosts a few motels and camp sites, a licenced restaurant and pub, and workshop/petrol station. With the sun setting, and enjoying a beer at the local watering hole, we bumped into Doug Sprigg – custodian, director of Arkaroola for the past 50 years, and son of the late Reg Sprigg. Doug is passionate about the local region, and a veritable font of knowledge. He’s also an avid astronomer – a great pastime up here, with Arkaroola recently becoming South Australia’s first international dark sky sanctuary. He happily gives us a tour of the local town – and distant galaxies, through an impressive telescope.

© 2024. This work is openly licensed via CC BY-NC 4.0

© 2024. This work is openly licensed via CC BY-NC 4.0

© 2024. This work is openly licensed via CC BY-NC 4.0

© 2024. This work is openly licensed via CC BY-NC 4.0

Outback life

The week settles into a routine: early mornings checking on traps and taking wallaby measurements, the middle of the day exploring the beautiful landscapes and wildlife of the Flinders Ranges, before setting and baiting the traps before sunset. Warm evenings spent outside enjoying the company, wine, and endless stars.

© 2024. This work is openly licensed via CC BY-NC 4.0

© 2024. This work is openly licensed via CC BY-NC 4.0

© 2024. This work is openly licensed via CC BY-NC 4.0

© 2024. This work is openly licensed via CC BY-NC 4.0

© 2024. This work is openly licensed via CC BY-NC 4.0

© 2024. This work is openly licensed via CC BY-NC 4.0

© 2024. This work is openly licensed via CC BY-NC 4.0

Before I know it, our time in the Flinders comes to an end. After a few hours lugging the traps back down from the rocky landscape and cleaning them, they’re loaded back on the trailer, and we make the long journey home to Adelaide. The long trip back gives me plenty of time to contemplate the week and absorb what has been a truly amazing experience. It’s certainly opened my eyes to the sheer beauty of Australia’s rugged arid landscape, and an appreciation for the animals and plants that make it their home.

© 2024. This work is openly licensed via CC BY-NC 4.0

© 2024. This work is openly licensed via CC BY-NC 4.0

A bounce back?

What does the future hold for this wallaby species? Human-induced climate change is likely to alter their habitat, making an already tough habitat tougher. However, knowing that there are passionate people out there looking after the landscape and animals, and organisations running successful programs like Bounceback fills me with hope. I believe that it’s our collective responsibility to ensure that these remarkable landscapes and animals are preserved, and that they can be enjoyed by future generations.

© 2024. This work is openly licensed via CC BY-NC 4.0

I hope you enjoyed this retrospective story. There are a few other Australian field trips that I’ll be sharing the future. Stay tuned also for an update on what Lauren found about the YFRWs in the region during her PhD.

Photo of the month

Technically not taken in June 2024! But part of the trip from the retrospective story. The person in frame climbing gives a sense of scale. You can also see a dry river down below. Every year or two there’ll be a large rain storm that sees water invigorate this arid landscape.

© 2024. This work is openly licensed via CC BY-NC 4.0

![Red kangaroo, the largest living macropodid. fir0002 flagstaffotos [CC BY-NC], via wikipedia.org](photos/redkanga.jpg)

![Rufous hare-wallaby (Mala). Michael Hains, some rights reserved [CC BY-NC], via iNaturalist.org](photos/rufous.png)